Fuel supply at the petrol pump is the culmination of many production processes, physical movements and changes of ownership that come together to ensure we can get the fuels we need when we want them.

Once crude oils have been extracted (the “upstream”), there are three separate but interconnected markets, which hydrocarbons tend to pass through before finished products are supplied to the final consumer. These are the international commodities markets for i) crude oil and ii) refined fuels as well as the market provided by iii) forecourt retailers, which set the final prices at the pump. These markets are highly competitive, ensuring the UK consumer pays a fair price for the petrol and diesel they buy.

The price of crude oil used by refiners to manufacture diesel and petrol, and the sale price for these refined products are typically set within the commodity markets by external benchmarking companies. As such, refiners can be considered to be ‘price takers’ rather than price setters because they sell their products into a market with an existing benchmarked price.

These benchmark prices are subject to sudden changes caused by geopolitical events; for example, wars, sanctions, or trade disputes. As such, refining margins tend to be cyclical. For example, the UKPIA 2022 Statistical Review shows that global restrictions imposed to control the spread of the Covid-19 virus caused demand to decrease substantially for nearly all refined fuel products in 2020 and our members saw net losses of £1.8 billion.

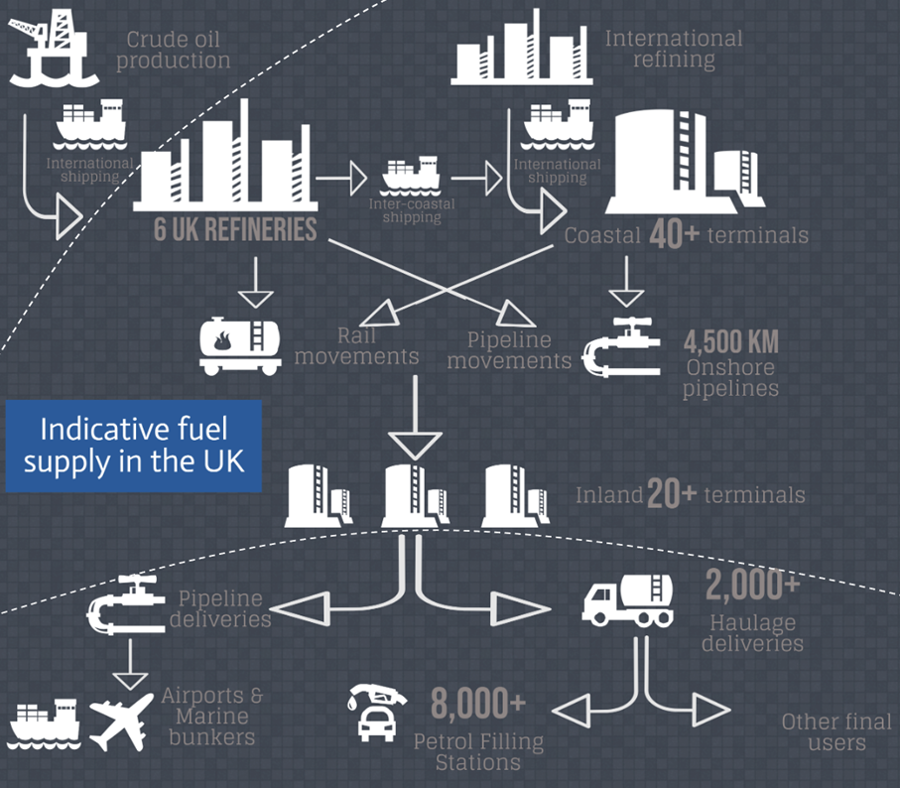

The journey of hydrocarbons to the consumer

The supply chain of petrol or diesel and other hydrocarbon products is not simply a case of digging it out of the ground and sending it to the forecourt. To make the feedstocks for fuels useful (mainly crude oil, but increasingly renewable sources such as biofuels) they need to be refined into specific products which meet certain uses, and be moved from the refinery to the final consumer, which may be in another country or even continent.

Refining

Crude oil formed millions of years ago from small aquatic plants and animals. When the organisms died, they settled on the ocean or river floor and became a rich organic bed which eventually turned into sedimentary rock.

Refining takes crude oil and biofuels and makes market-grade products in the quality and quantities needed. This is possible because crude oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons that boil at different temperatures. As the vapours cool they can be separated into various streams of similar sized molecules, which can be transformed into different products such as petrol and diesel.

Refining has three stages. First is the ‘separation stage’ which takes raw oil and separates it into batches of similar-sized molecules using a refinery unit called a distillation column. These batches of similar-sized molecules are known as fractions or cuts.

Next is the ‘conversion stage’ which takes the fractions or cuts and produces blending components. There are different types of conversion; ‘cracking’ takes complex molecules and breaks them into smaller, lighter molecules; ‘rearranging’ changes the shape of hydrocarbon molecules to give it different properties; and ‘combining’ makes larger molecules from smaller ones.

Finally, is the blending stage which creates the finished market products like petrol, diesel, jet fuel and heating oil [MENNTA Energy Solutions].

Trade and bulk movement of fuels

The downstream oil sector manages the import, refining, storage, distribution and retail of petrol, diesel, aviation, heating fuels and other petroleum products. It ensures that fuel supplies are always available for use across the UK.

A 3,000-mile network of pipelines is used to move large volumes of refined products from the UK’s six refiners to 60 storage terminals. Coastal tankers, often small enough to navigate shallower waters and dock at coastal ports, also transport large quantities of product to terminals. In addition, several UK refineries have rail connections that allow refined products to be transported to rail-fed terminals across the country.

The downstream sector supplies and distributes 96% of the UK’s transport fuel through a mix of domestic production 55% and imports 45%. This includes the low carbon fuels that reduced greenhouse gasses by the equivalent of taking 2.5 million cars off the road in 2020 [UKPIA Statistical Review 2022].

Road transport is used to deliver most products to the end user, whether that’s a forecourt or an industrial consumer, using tankers capable of carrying up to 40,000 litres.

Delivery to the final consumer

The UK has around 8,400 filling stations that provide the general public and businesses with the road transport fuels they need.

Petrol retailing is a highly competitive business. The growing presence of supermarkets has led to a significant change for the sector, with their share of the retail fuels market growing from 11% in 1992 to around 45% in 2018.

The supermarkets' growth in market share has coincided with a rapid expansion in their large out-of-town stores, whilst smaller and more remote filling stations have closed, with the number of filling stations in the UK falling from about 19,000 in 1990 to 8,422 in 2017 although numbers have remained relatively stable since that time.

See our Future Vision of the sector: Here

Frequently asked questions

How long it takes for changes to wholesale prices, and fuel duties to be reflected in pump prices for petrol and diesel?

In its 2013 report, the Office for Fair Trading (OFT), the forerunner to the Competitions and Market’s Authority (CMA), concluded that the length of time to pass from crude oil to refinery prices was variable, but it seemed to take approximately two weeks, while the pass through appeared longer for refineries to pump prices, with most of the cost seemingly passed through by 5 weeks. These figures were noted to be the same regardless of a price rise or fall.

How has the forecourt supply chain changed over the past decade?

There has been relatively little change in the market share of different types of forecourt ownership in the last decade with the overall number of forecourt sites remaining relatively stable above the 8,000 mark.

Other interesting links:

Fuels Industry UK 2023 Statistical Review: Here

MENNTA Energy Solutions: Here